The missal we

currently use was published in 1973 and has served the Church well for nearly 40 years. However over

that time there has been much discussion of the need to revise this initial translation of

the Latin into English in order to recapture more accurately the meaning and poetry of the

original Latin texts and their allusions to Scripture. In 2001 the Vatican published guiding

principles for translating the Latin Missal into other languages. This new translation follows

these guidelines and will adhere more closely to the Latin text. It will be more formal at times

but will provide a richer and more nuanced translation of our rich heritage of prayer

that is contained in the Roman Missal.

The missal we

currently use was published in 1973 and has served the Church well for nearly 40 years. However over

that time there has been much discussion of the need to revise this initial translation of

the Latin into English in order to recapture more accurately the meaning and poetry of the

original Latin texts and their allusions to Scripture. In 2001 the Vatican published guiding

principles for translating the Latin Missal into other languages. This new translation follows

these guidelines and will adhere more closely to the Latin text. It will be more formal at times

but will provide a richer and more nuanced translation of our rich heritage of prayer

that is contained in the Roman Missal.

Who is doing the work

of translation?

The work of

translation has been done by a group of Bishops specialising in translation and

linguistics. The

International Commission for English in the Liturgy (ICEL) has translated the

Latin into English and

then submitted the drafts to all the Bishops of the English speaking

world. Finally the

translation has been approved by the Vatican Congregation for Divine

Worship and the

Sacraments with the assistance of a committee called Vox Clara.

Is this Missal the

Vatican II Missal?

It is most definitely

the Vatican II Missal. It is the same missal which was produced in 1970

and revised on two

later occasions. It is the translation into English that has changed not the

original prayers of

the Mass.

Will it sound very

different?

Yes, it will. Not only

will the people’s responses change but the prayers said by the priest will

also change. The

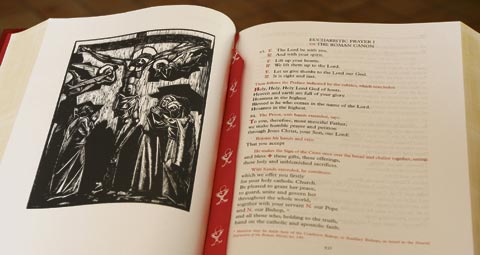

Eucharistic Prayers will sound different. Remember, it is not the original

Latin Missal that has

changed only the translation. So it will be the same Mass that we have

had since Vatican II

but it will sound different.

Will there be any

changes in posture?

No, any changes in

posture have already been introduced in recent years. Therefore you will

continue to sit, stand

and kneel as you have always done.

How will we know the

new responses?

There will be pew

cards produced throughout Australia to assist the people with responses.

Some Churches have

data projectors that may also assist with the people’s responses.

Will the readings

change?

At this stage the

readings will remain the same. In a few years time the Lectionary will be revised and the

translation of the readings will change then.

When can I buy a new

Missal for my personal use?

The new Missal for use

by the priest during Mass will be printed in the latter half of 2011. The new

version of the readings will not be available for a few years. Publishers will

publish personal missals soon.

Will there be one book

for the Missal or will it be several volumes?

The Missal will be in

one volume. Eucharistic Prayers for Children will be published in a

separate supplement.

Will there be many

changes?

For the people the

changes are minor ones. For the priest, however, the changes involve all

the Prayers and the

Eucharistic Prayers and are quite extensive.

Will there be a cost

involved?

Yes, Parishes will

need to budget for the cost of the new Missal and also for pew cards and

music for new Mass

settings.

How will we sing the

parts of the Mass when there are new words?

New Mass settings have

been written by Trinidadian and international composers. There is also

a chant setting in the

Missal.

Will Communion of the

Sick change?

Yes, wherever parts of

the Mass are used the words will change. Texts used at Weddings and

Funerals will also

change.

Why do we say consubstantial

in the Nicene Creed?

In the new translation

of the Nicene Creed, “consubstantial with the Father” replaces the

expression “of one

Being with the Father”, in speaking about the Lord Jesus Christ. The

nature of the

relationship between God the Father and God the Son, and the truth of the Son’s

divinity, are most

important aspects of the Christian faith, and Councils such as Nicaea

(325ad) and Calcedon

(451ad) were held to address these questions and to discern and

express the orthodox

belief of the Church.

The difficulty in

expressing in an acceptable way the relationship between God the Father and

God the Son required

the early bishops and theologians to give new subtleties of meaning to

existing Greek and

Latin words. The expression “of one Being with the Father” in the current

translation of the

Nicene Creed is not always thought to convey the meaning of the Latin

consubstantialis, nor

indeed the original Greek homoousios which it referred to, in a

satisfactory way. Some

Latin words have meanings which are simply not readily translatable

into ordinary English.

The metaphysical concepts of “essence”, “being” and “substance”, of

which consubstantialis

and homoousios speak are not straightforward and in fact they are

easily misunderstood

because their theological meaning is not exactly the same as their

meaning in ordinary

English. “Consubstantial”, which has been chosen in the revised

translation of the

Creed’s Latin consubstantialis, has a genuine and distinct theological

meaning. It is not a

common word in English, but is being used to identify and express a

unique relationship.

Why is it that we say

“through my fault...” three times in the Confession... isn’t that too

repetitive?

The simplest answer

is, because that is what the Latin has ‐ but that does not really cast any

light on the matter.

Simple versions of the Confiteor are found from the 700s. The phrase

"mea culpa"

(through my fault) first appeared in about AD 1080, and it remained in this

single form in the

liturgies of the Carmelites and Dominicans until modern times, and in the

Roman missal until the

1500s. The version "mea culpa, mea maxima culpa" is attributed to St

Thomas Becket (died

1170). The triple form only entered the Roman Missal in 1570. We can

only speculate about

why it evolved into the triple form. It is sometimes said that we like to

tripled things in

honour of the Trinity, but intensifying by triplication seems to be a common

human practice. In

some contexts this results in the triple recitation of a whole prayer or an

action. Another

example of triple intensification in our liturgy actually predates the liturgy

because it is a direct

citation of Isaiah 6:3, "Holy, Holy, Holy." Some three‐fold elements

result from reducing a

litany to its minimum form. The best example is "Lamb of God" which

we say three time, but

when it was introduced in about AD 800 it was as a litany sung

continuously until the

breaking of all the consecrated bread was finished. Other forms of

intensifying

triplication are found in our Mass, but with some variation each time, such as

in

the Roman Canon

(Eucharistic Prayer 1) "these gifts, these offerings, these unblemished

sacrifices".

Similarly on Good Friday we find the ancient Trishagion (Thrice‐holy) in "Holy

is God, Holy and

Mighty, Holy and Immortal." It appears that the role of such triplications

is

to intensify our focus

on some element. The repetition and expansion in "through my fault,

through my fault,

through my most grievous" thus has the effect of making us pause, in a

sense, to really acknowledge

what we are saying. It helps it "sink in", so to speak.

Why do we only say “It

is right and just” in the dialogue before the Preface of the

Eucharistic Prayer?

Again this translation

reflects the precise words of the Latin text. The Preface will then take

up this phrase and

repeat it as its opening words: “It is truly right and just, our duty and

salvation…” To

appreciate this connection between the words of the assembly and the

Preface, we need to

understand the role of the faithful in the Eucharistic Prayer – they are not

silent spectators, but

must be participants who make their thanksgiving to God. St. John

Chrysostom (died 407

ad) writes: “The offering of thanksgiving again is common, for the

priest does not give

thanks alone but all the people join him in doing so. Once they respond

by assenting that it

is ‘right and just’, he begins the thanksgiving”. Once the assembly has

assented that is right

and just to give thanks, the priest can begin the Eucharistic Prayer

because the assembly

provide living witness to his words of thanks. Because of the living

faith of the assembly,

“it is truly right and just” to give thanks to God.

Why is our response

now “And with your spirit” in the greetings?

This is an accurate

translation of the Latin text and is reflected in other language translations.

To understand this

translation it is helpful to look at the meaning of this phrase in our

tradition:

1. “In the most sacred

mysteries themselves (the Mass), the priest prays for the people who

in turn pray for him

since this is the meaning of the words, ‘And with your spirit’”, writes St.

John Chrysostom (died

407 ad).

2. Chrysostom also

writes, “If there were no Holy Spirit, there would be neither shepherds

nor teachers in the

Church ... You acclaimed, ‘And also with your spirit’. You would not have

done this unless the

Holy Spirit were actually dwelling within him”.

3. “They reply ‘And

with your spirit’. In this way they make known to the bishop and to all

that not only do

others need a blessing and the bishop’s prayer but that the bishop himself also

needs the prayer of

all… This is why the bishop blesses the people at the ‘peace’ and then

receives their

blessing as they respond, ‘And with your spirit’”. These words come from

Theodore of Mopsuestia

(died 428 ad).

Thus when the assembly

respond to the words, “The Lord be with you”, they communicate

something of mutual

importance between the ordained and themselves. They mutually

confirm the presence

of the Lord who unites them and who is the Supreme Celebrant of the

holy mysteries. This

is made possible by the gift of the Holy Spirit to the ordained and to the

faithful.

Apostles’ Creed - “He

descended into hell”

This brief and

matter-of-fact statement holds the promise of immense hope for believers. It asserts that Jesus

Christ not only died our death but also entered the realm of the dead and set them free. This “hell”

is not the hell of later popular imagination – the fiery hell of eternal

punishment – but the

hell of the scriptures, Hades or Sheol, the shadowy domain where the dead are spiritless

and lost, cut off from light and life. Dwelling with the dead Jesus brings his life-giving love

to bear on all the powers of darkness and disarms them. Nothing in the cosmos is excluded

from this victory, as Paul writes, “I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor

rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all

creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus

our Lord” (Roms 8:38-39).