In the celebration of Mass we raise our

hearts and minds to God. We are creatures of body as well as spirit, so our

prayer is not confined to our minds and hearts. It is expressed by our bodies

as well. When our bodies are engaged in our prayer, we pray with our whole

person. Using our entire being in prayer helps us to pray with greater

attentiveness. During Mass we assume different postures—standing, kneeling,

sitting—and we are also invited to make a variety of gestures. These postures

and gestures are not merely ceremonial. They have profound meaning and, when

done with understanding, can enhance our participation in the Mass.

STANDING

Standing is a sign of respect and honor,

so we stand as the celebrant who represents Christ enters and leaves the

assembly. From the earliest days of the Church, this posture has been

understood as the stance of those who have risen with Christ and seek the

things that are above. When we stand for prayer, we assume our full stature

before God, not in pride but in humble gratitude for the marvelous things God

has done in creating and redeeming each one of us. By Baptism we have been

given a share in the life of God, and the posture of standing is an

acknowledgment of this wonderful gift. We stand for the proclamation of the

Gospel, which recounts the words and deeds of the Lord. The bishops of the

United States have chosen standing as the posture to be observed for the

reception of Communion.

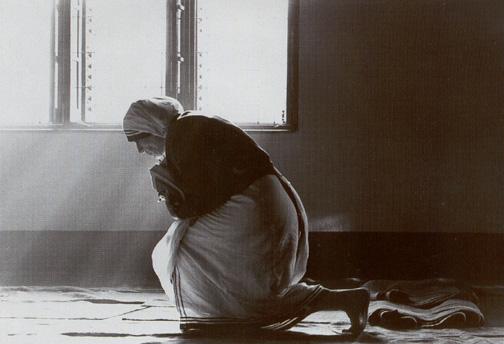

KNEELING

In the early Church, kneeling signified

penance. So thoroughly was kneeling identified with penance that the early

Christians were forbidden to kneel on Sundays and during the Easter season,

when the prevailing spirit of the Liturgy was one of joy and thanksgiving. In

the Middle Ages kneeling came to signify homage, and more recently this posture

has come to signify adoration, especially before the presence of Christ in the

Eucharist. It is for this reason that the bishops of this country have chosen

the posture of kneeling for the entire Eucharistic Prayer

SITTING

Sitting is the posture of listening and

meditation, so the congregation sits for the pre-Gospel

readings and the homily and may also sit for the period of meditation following

Communion. All should strive to assume a seated posture during the Mass that is

attentive rather than merely at rest.

PROCESSIONS

Every procession in the Liturgy is a

sign of the pilgrim Church, the body of those who believe in Christ, on their

way to the Heavenly Jerusalem. The Mass begins with the procession of the

priest and ministers to the altar. The Book of the Gospels is carried in

procession to the ambo. The gifts of bread and wine are brought forward to the

altar. Members of the assembly come forward in procession—eagerly, attentively,

and devoutly—to receive Holy Communion. We who believe in Christ are moving in

time toward that moment when we will leave this world and enter into the joy of

the Lord in the eternal Kingdom he has prepared for us.

MAKING

THE SIGN OF THE CROSS

We begin and end Mass by marking

ourselves with the Sign of the Cross. Because it was by his death on the Cross

that Christ redeemed humankind, we trace the Sign of the Cross on our

foreheads, lips, and hearts at the beginning of the Gospel, praying that the

Word of God may be always in our minds, on our lips, and in our hearts. The

cross reminds us in a physical way of the Paschal Mystery we celebrate: the

death and Resurrection of our Savior Jesus Christ.

BOWING

Bowing signifies reverence, respect, and

gratitude. In the Creed we bow at the words that commemorate the Incarnation.

We also bow as a sign of reverence before we receive Communion. The priest and

other ministers bow to the altar, a symbol of Christ, when entering or leaving

the sanctuary. As a sign of respect and reverence even in our speech, we bow

our heads at the name of Jesus, at the mention of the Three Persons of the

Trinity, at

the name of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and at the name of the saint whose

particular feast or memorial is being observed.

GENUFLECTING

As a sign of adoration, we genuflect by

bringing our right knee to the floor. Many people also make the Sign of the Cross

as they bend their knee. Traditionally, Catholics genuflect on entering and

leaving church if the Blessed Sacrament is present in the sanctuary of the Church.

The priest and deacon genuflect to the tabernacle on entering and leaving the

sanctuary. The priest also genuflects in adoration after he shows the Body and

Blood of Christ to the people after the consecration and again before inviting the

people to Holy Communion.

ORANS

The priest frequently uses this ancient

prayer posture, extending his hands to his sides, slightly elevated. Orans means

“praying.” Early Christian art frequently depicts the saints and others

standing in this posture, offering their prayers and surrendering themselves,

with hands uplifted to the Lord, in a gesture that echoes Christ’s outstretched

arms as he offered himself on the Cross.

PROSTRATING

In this rarely used posture, an

individual lies full-length on the floor, face to the ground. A posture of deep

humility, it signifies our willingness to share in Christ’s death so as to

share in his Resurrection (see Rom 6). It is used at the beginning of the Celebration

of the Lord’s Passion on Good Friday and also during the Litany of the Saints in

the Rite of Ordination, when those to be ordained deacons, priests, and bishops

prostrate themselves in humble prayer and submission to Christ.

SINGING

“By its very nature song has both an

individual and a communal dimension. Thus, it is no wonder that singing together

in church expresses so well the sacramental presence of God to his people”

(United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Sing to the Lord, no. 2). As we

raise our voices as one in the prayers, dialogues, and chants of the Mass, most

especially in the Eucharistic Prayer, as well as the other hymns and songs, we

each lend our individual voices to the great hymn of praise and thanksgiving to

the Triune God.

PRAYING

IN UNISON

In the Mass, the worshiping assembly

prays in one voice, speaking or singing together the words of the prayers. By saying

the same words at the same time, we act as what we truly are—one Body united in

Christ through the Sacrament of Baptism.

BEING

SILENT

“Silence in the Liturgy allows the

community to reflect on what it has heard and experienced, and to open its heart

to the mystery celebrated” (Sing to the Lord, no. 118). We gather in silence,

taking time to separate ourselves from the concerns of the world and enter into

the sacred action. We reflect on the readings in silence. We may take time for

silent reflection and prayer after Holy Communion. These times of silence are

not merely times when nothing happens; rather, they are opportunities for us to

enter more deeply in what God is doing in the Mass, and, like Mary, to keep

“all these things, reflecting on them” in our hearts (Lk 2:19).

CONCLUSION

The Church sees in these common postures

and gestures both a symbol of the unity of those who have come together to

worship and also a means of fostering that unity. We are not free to change

these postures to suit our own individual piety, for the Church makes it clear

that our unity of posture and gesture is an expression of our participation in

the one Body formed by the baptized with Christ, our head. When we stand,

kneel, sit, bow, and sign ourselves in common action, we give unambiguous

witness that we are indeed the Body of Christ, united in body, mind, and voice.

REFERENCE

United States Conference of Catholic

Bishops (USCCB). Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship. Pastoral Liturgy

Series 4. Washington, DC: USCCB, 2007.

Scripture texts used in this work are

taken from the New American Bible, copyright © 1991, 1986, and 1970 by the

Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, DC 20017

No comments:

Post a Comment